Blog

Vagus Nerve and PEMF – The Science Behind

The vagus nerve, often referred to as the “superhighway” of the parasympathetic nervous system, plays a vital role in regulating inflammation, heart rate, digestion, and [...]

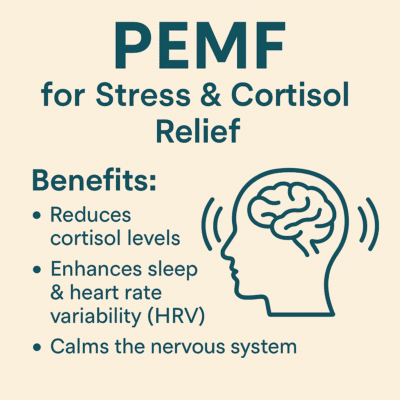

The Role of PEMF in Reducing Cortisol

In today’s high-stress, fast-paced world, finding natural ways to calm the nervous system and regulate stress hormones is essential. Pulsed [...]

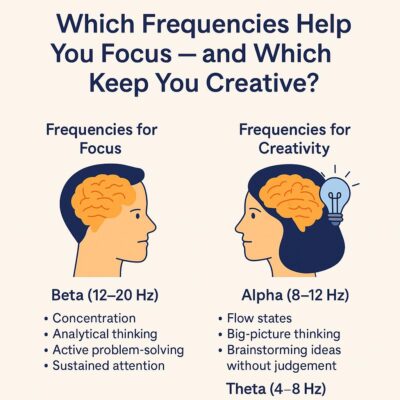

Which Frequencies Help You Focus – and Which Keep You Creative?

When it comes to mental performance, not all brainwaves are created equal. Whether you’re trying to dive into deep work, [...]

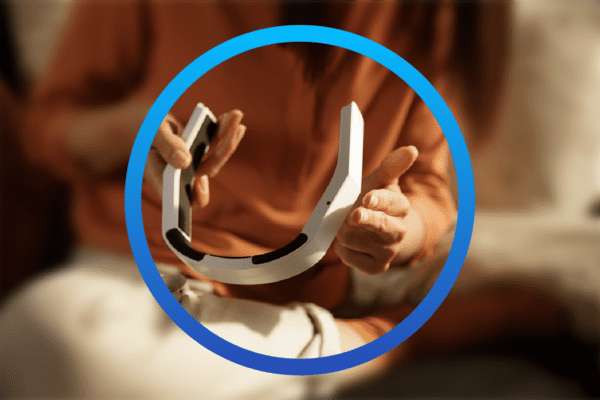

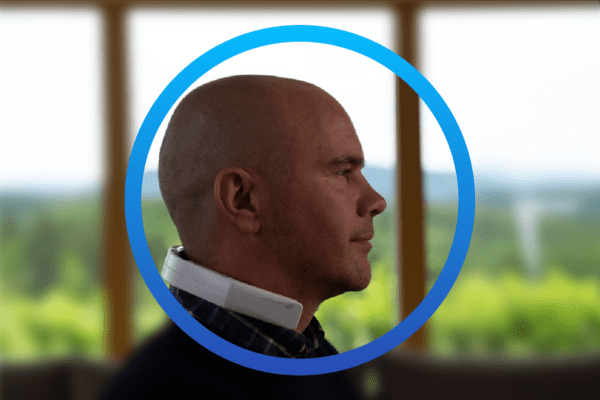

The Best Vagus Nerve Stimulator? Comparing NeoRhythm to Nurosym, Gammacore, Pulsetto, and Sensate

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has gained traction as a non-invasive therapy for enhancing overall well-being. While several devices claim to [...]

The Best Athletes Are Already Using PEMF

In the highly competitive world of sports, athletes continuously seek cutting-edge methods to improve performance, speed up recovery, and maintain [...]

How Nutrition Affects Inflammation and Pain – And How PEMF Can Help

Chronic inflammation is at the root of many health problems, including persistent pain, autoimmune disorders, and metabolic diseases. While medication [...]

How to Combine Nutrition and PEMF for Deep Regeneration and Better Sleep

Sleep is one of the most important components of our health and well-being, yet more and more people face insomnia [...]