Exploring PEMF and Red Light Therapy

Introduction In the realm of alternative therapies for health and wellness, both therapies have gained significant attention and…

Do you trust your gut? In these moments when you know you know the answer, but you don’t know why, do you follow your instincts? Research on decision-making shows that in most situations people are likely to follow their hunch. Intuition became the buzzword of popular life coaching sites or new-age spiritual gurus. It’s being […]

Do you trust your gut?

In these moments when you know you know the answer, but you don’t know why, do you follow your instincts?

Research on decision-making shows that in most situations people are likely to follow their hunch. Intuition became the buzzword of popular life coaching sites or new-age spiritual gurus. It’s being referred to as “inner voice” or “sixth sense”.

Is your intuition reliable, though?

Table of Contents

When you’re driving on an empty road, your brain relies on automatic reactions to stop when required or follow directions. Your neural processing is fast and intuitive. But when you drive on a busy highway, your brain needs to employ more resources to navigate traffic, predict potentially dangerous situations, and listen to directions from GPS. Your mode of thinking becomes more analytical.

Studying how people make decisions in the field of economics, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversk noticed that most of the decisions we make are done without thinking: in other words, intuitively. They are guided by mental shortcuts called heuristics.

According to Kahneman, there are two modes of thinking.

Intuitive thinking evolved for obvious reasons: its fast processing is cost-efficient and saves time. Because intuition requires very little mental effort, System 1 is the main operator of the brain. It is based on our learned responses and mental shortcuts.

It often forms our first impressions of situations and people we get in contact with and guides our responses.

Putting it briefly, intuition is the rapid, intuitive, automatic response. In many standard situations, it is also good enough to provide the right answer. When the brain decides that it’s necessary, system 2 takes over and analytical thinking kicks in.

It stops the automatic processing of system 1 and engages in a controlled exploration of alternative decisions.

What is interesting, intuition and analytical thinking are linked to two separate patterns of brainwaves. System 1 thinking is characterized by an increase in Alpha waves, which reflects access to long-term memory and the release of attentional resources.

On the contrary, during analytic thinking, an increase in Theta waves can be observed, which is a clear sign of engaging mental control over thoughts and working memory.

For scientists, these observations were not surprising. Other studies noted a decreased Alpha activity whenever attention was recruited. After all, Alpha waves are the hallmark of daydreaming, as we’ve discussed in a previous article.

Conversely, an increase in Alpha marks automatic access to knowledge and long-term memory. Similarly, Theta waves increase when working memory is used. The more thoughts or ideas need to be remembered, manipulated, or altered, the more Theta activity can be observed.

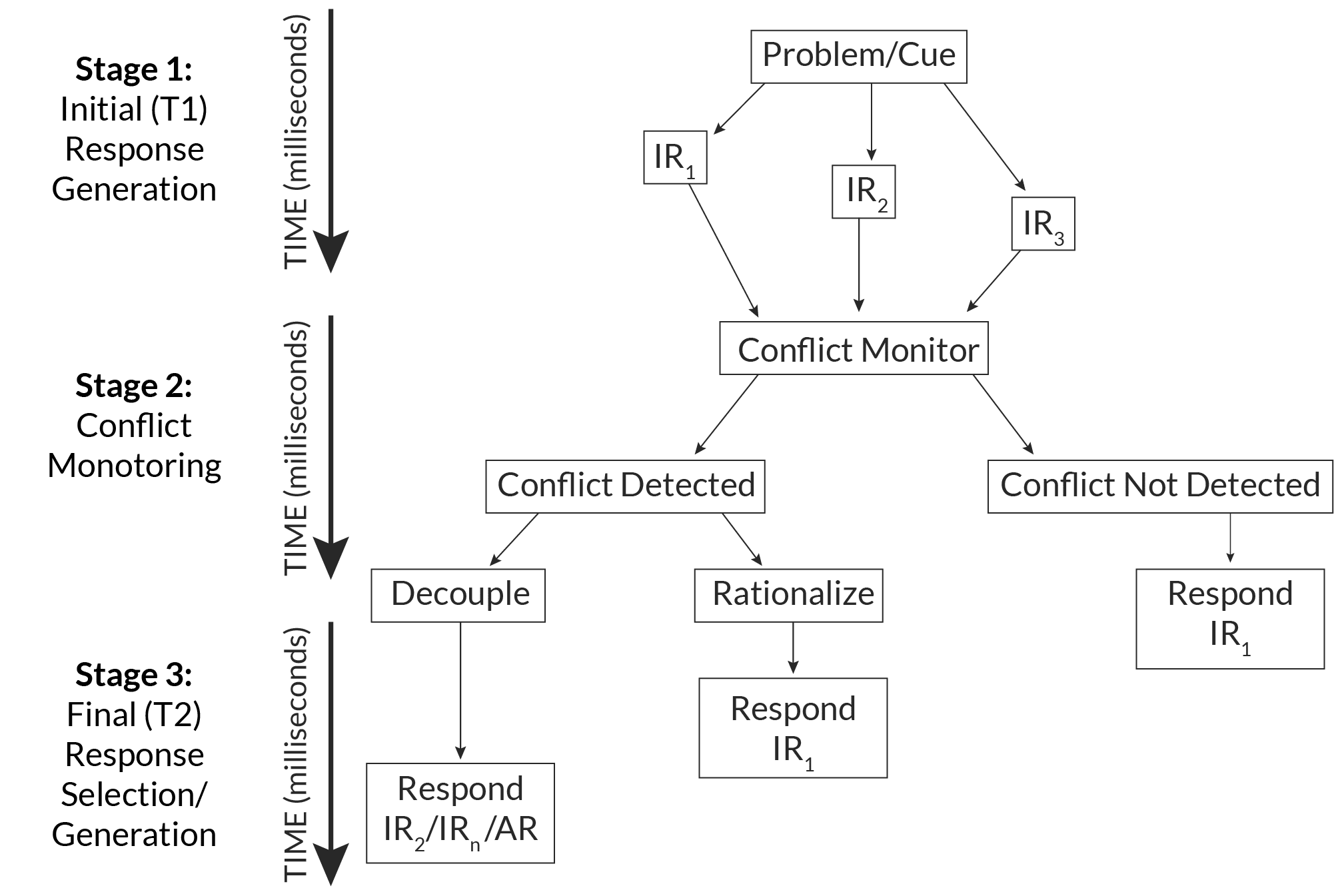

Further exploration of how Level 1 and Level 2 processes work in the brain led to the conclusion that decision-making has three stages.

Whenever you face a new problem, at the first stage the automatic processes of your intuition kick in. Based on your knowledge and past experiences, your mind generates intuitive solutions.

Then comes the phase of conflict monitoring. Does your initial intuitive response make sense? If it feels doubtful, the brain switches to the third stage. Analytic thinking, AKA the Level 2 system, comes into play.

The engagement of rational thought can yield two outcomes. The first one is decoupling: leaving the initial intuitive solution aside and instead coming up with a more thoughtful answer to the problem. However, quite often the opposite scenario happens – rationalization. Instead of finding a better alternative, your mind can be eager to justify your first answer, coming up with seemingly reasonable reasons for why the intuitive answer was right.

Why do our brains rationalize potentially wrong choices? A possible solution is that it just feels more comforting to be right. Translating it into more scientific terms, and falsifying your answers may often come with a higher emotional cost.

As you can see, in typical decision making the first solutions are generated intuitively. Whether logical reasoning will come into play depends on detecting potential conflicts. Even then, sometimes logic gets employed only to rationalize intuitive responses. The true power of intuition lies in how difficult it is for us to look beyond our instincts.

Source: Pennycook, G., Fugelsang, J. A., & Koehler, D. J. (2015). What makes us think? A three-stage dual-process model of analytic engagement. Cognitive Psychology, 80, 34–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2015.05.001

Source: Pennycook, G., Fugelsang, J. A., & Koehler, D. J. (2015). What makes us think? A three-stage dual-process model of analytic engagement. Cognitive Psychology, 80, 34–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2015.05.001

A few months after the US invasion of Iraq, G.W. Bush was confronted by his advisors who raised concerns about a range of problems linked to the newly started war. The president disregarded their arguments, ensuring that all was well and that the US was on the right course. His advisor asked: “How can you be so sure when you know you don’t know the facts?”, to which G.W. Bush replied: “My instincts.”

The US president’s faith that his gut feeling is more trustworthy than the analysis of his advisors is a perfect example of how dangerous intuition can get when the stakes are high. It seems that a big deal of our social life is guided by decisions made on the spot. The research on decision-making started by Kahneman and then continued by others gave a solid explanation to the phenomenon observed by economists for a long time: that the decisions of investors are often guided not by deliberate reasoning, but by intuitive thinking. Investors fall prey to the heuristic of representativeness, particularly relying on extrapolation: they expect the trends to continue.

Observing how intuition works in investing we may conclude that cheap brain processing leads to costly errors. Similarly, intuition guides the everyday choices of thousands of people, leading them to make decisions that impact whole societies.

A group of scientists from Canada examined the attitudes of people who endorse anti-vaccination attitudes and found that they are less likely to use analytical reasoning in problem-solving quizzes. This negative correlation between anti-vaccine beliefs and rational thinking was significant even when the scientists ruled out other factors like sex, education, and religiosity.

Is intuition so bad? Of course not. It serves as an energy-efficient and fast way of making decisions. If we would rationally ponder upon every choice, we would be… very slow creatures.

There is also a chance that you are an avid reader of the self-help niche, you’ve heard many times about following your intuition and obtained great changes in your life by doing that. You may feel somewhat angry reading my ruthless, cold, and scientific dissection of automatic thinking.

To this, I respond: blame the word.

In popular literature, the term “intuition” is vague, imprecise, and used to describe a wide range of behaviors that have little to do with intuition. Doing what you want to do in life is not “intuition”, but rational choice. Observing the feelings of your body and reacting to them is not “intuition”, but being mindful.

You shouldn’t be worried about intuition itself. The real danger lies in trusting it. Intuition can lead to brilliant inspirations, but also to terrible mistakes.

However, there is good news too. Asking people to pause and think about their choices can work miracles. A group of scientists from Chicago managed to reduce violent crime and arrests in a group of economically disadvantaged youth by teaching them to downgrade their intuitive reactions. The youngsters were taught to slow down and reflect on whether their automatic thoughts and behaviors are well suited to the situation they are in.

How to make use of this knowledge? We have very solid evidence that Theta brainwaves are connected with System 2 thinking, mental control over thoughts, and the performance of working memory. We don’t know yet if stimulating Theta will be accompanied by an increase in analytic thinking… but it is very likely. If you would like to give it a try, consider using a PEMF device during your next session of problem-solving. To increase Theta, you can choose one of the predefined programs such as Theta Meditation, Mindfulness Meditation, and Open-Heart Meditation. You can also set a custom frequency between 4 and 7 Hz.

Williams, C. C., Kappen, M., Hassall, C. D., Wright, B., & Krigolson, O. E. (2019). Thinking theta and alpha: Mechanisms of intuitive and analytical reasoning. NeuroImage (Orlando, Fla.), 189, 574–580.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.048

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow (1.ed. ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Pennycook, G., Fugelsang, J. A., & Koehler, D. J. (2015). What makes us think? A three-stage dual-process model of analytic engagement. Cognitive Psychology, 80, 34–72.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2015.05.001

Heller, S. B., Shah, A. K., Guryan, J., Ludwig, J., Mullainathan, S., & Pollack, H. A. (2017). Thinking, fast and slow?: Some field experiments to reduce crime and dropout in Chicago. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1), 1–54.

https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw033

Caravaggio, F., Porco, N., Kim, J., Fervaha, G., Graff-Guerrero, A., & Gerretsen, P. (2021). Anti-vaccination attitudes are associated with less analytical and more intuitive reasoning. Psychology, Health & Medicine, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.2014911

NeoRhythm has not been evaluated by the FDA. These products do not claim to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any medical conditions. Always consult your medical doctor regarding any health concerns.