Why Does Your Mind Wander?

Struggling with distractions? Explore the profound reasons behind your wandering mind and uncover strategies to boost focus and creativity. Discover how to navigate the modern world’s attention challenges!

You know that feeling: you’re trying to focus, but your mind is all over the place.

You are trying to be productive at work, or just read a book in your leisure time, and there is constantly something taking your attention away. It’s even worse when you’re trying to meditate. The moment you close your eyes, thousands of thoughts come rushing into your mind, as if your malignant brain is trying to turn your contemplative session into misery.

Itchy thoughts

Table of Contents

If you consciously pay attention to what happens in your mind when it gets distracted, you will notice an “itch”.

An itch to browse through social media or to check on the news. The fear of missing out. When you are doing tasks that are monotonous or difficult, your brain craves novelty, for something flashing and blinking that will take it away from the mundane activity. The habitual reaction is to scratch that itch. Browse and update.

Does it help?

It only makes the itching worse. The brain gets used to the relentless cycle: trying to get focused, feeling the itch, scratching it, getting updated. For most people when they’re working, they only spend around half the time actually doing the tasks they set out to do. During the rest of that time, their minds travel in time, contemplating past memories or simulating scenarios of the future.

I doubt if you can read through this article without getting distracted at least once. Don’t treat it as a challenge, though.

The reason for these mental distractions is that the brain evolved to serve a primary goal: to solve problems. It likes to keep itself busy. When there are no problems to solve, it starts to wander, chewing on past problems or worrying about the future. It reflects on past events, reliving them and looking for meaning, trying to extrapolate successful behavior strategies from them. It conceptualizes and imagines future scenarios, visualizing desirable outcomes or simulating future problems.

Society has ADD

Jon Kabat Zinn, the therapist who adopted Buddhist meditation to start the mindfulness movement, said that “the whole modern society has ADD, attention deficit disorder”. The smart technology we’ve surrounded ourselves with craves our attention from every corner. We are used to constantly shifting our focus between windows on the computer screen and phone notifications. Obsessed with multitasking, we rarely do one thing at a time. Even chewing lunch or commuting from work, we mindlessly browse through the Internet, popping up a pill of the latest news. Whenever we feel lonely, we ingest a shot of dopamine harvesting social media likes and comments.

Our brains had to adjust to this technology-infused style of work, with short bursts of focus interspersed with distractions and mind wandering. The average attention span – the period you can sustain focus on one task – had become so short that we had to build a whole new environment to accommodate it. Modern media are designed to grab our attention for a moment and seize it with flashy images and constantly changing action, stripping down every bit of information so that it’s easily digestible.

Active at rest

It’s a logical assumption that when the brain is not engaged in performing any task, the level of neural activity drops down. You may imagine that it came as a shock when the brain imaging studies revealed that during the apparent “rest” time, quite a lot is going on in the brain. During some experiments, participants were asked to do mental tasks, interspersed with rest periods. The researchers expected to see less brain activity during no task times, but it turned out that when the participants were not engaged in any goal-oriented task, their brains got more active

Whenever your mental resources are not focused on one task, your brain starts to wander. That’s when a specific network in your brain, called the Default Mode Network, kicks in. It gets active when your attention is not focused on the external environment. Which, let’s face it, is quite often. Mind-wandering happens not only when your mind is resting, but also when you are doing repetitive or automatic tasks, like driving a car.

Default Mode Network incorporates many areas spread all around your brain. It evolved for processes that help you to be more efficient in your environment. Have you ever observed what is going on in your mind when you’re daydreaming? Your mind builds simulated scenarios involving yourself and other people or contemplates memories. For all these mental simulations of the future and past, the details are pulled from your memory. The goal of DMN’s activity is to extract information from your memory for the sake of problem-solving, finding patterns, and getting you prepared for whatever comes in the future.

Generating virtual reality is what your brain does well. Whenever you are dreaming, you enter a convincing, interactive playground. The kind of simulations that your brain does when you are mind-wandering are not as detailed and engaging as the night dreams, but they are created through a similar process that involves activating different memories and weaving them together to create new scenarios. Frankly, the name “daydreaming” is accurate: both when your mind wanders while awake and when you dream at night, the DMN is involved in generating your visions.

Creative dreaming

Even though daydreaming may seem counterproductive, it serves as a milieu for solving problems. Especially the ones that require creativity. Do you recall the last time you had a moment of insight? You’ve been struggling with a problem for a long time, and suddenly the solution came to your mind, and it felt so obvious and apparent…

The strokes of insight result from the background processing that happens when your mind is wandering. Most of it is unconscious. Even when you’re doing an undemanding task, the widespread network of DMN remains busy. It activates different corners of your memory network, combining various elements until the solution is found.

This means that when you’re dealing with a creative problem that requires searching for non-obvious solutions, the periods of doing nothing and staring out through the window are invaluable. (Good luck with telling it to your boss, though). Some research experiments have shown that when people are working on a difficult task, periods of daydreaming yield better results than actively trying to come up with an answer. Simply put, our brains need some time off from conscious, goal-oriented thoughts to be creative.

What if you don’t want your thoughts to wander? Daydreaming can be annoying, especially when you’re trying to complete some work but your mind keeps running away.

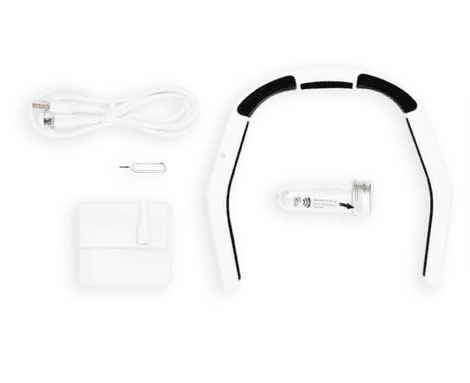

You can try to increase your focus using brainwave stimulation. Devices such as Neorhythm have specific programs designed to boost concentration. The mechanism is simple and non-invasive: a set of magnetic coils vibrate to strengthen the bandwidth of beta waves, which your brain emits when you’re mentally active and focused.

Another way to take control of your mind is through meditation. If you’re a beginner, trying to keep your mind calm and limit mental distractions will probably cause an upsurge of mind-wandering activity, which is precisely why meditation is such a good training ground for increasing focus. The key is not to block distractions but to train yourself in noticing them. To develop concentration, you need to be able to pinpoint the moments when your mind starts to wander and get it back on track.

References

Fox, Nijeboer, S., Solomonova, E., Domhoff, G. W., & Christoff, K. (2013). Dreaming as mind wandering: evidence from functional neuroimaging and first-person content reports. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 412–412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00412

Manning, & Steffens, D. C. (2016). Chapter 11 – Systems Neuroscience in Late-Life Depression. In Systems Neuroscience in Depression (pp. 325–340). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802456-0.00011-X

Hugdahl, Raichle, M. E., Mitra, A., & Specht, K. (2015). On the existence of a generalized non-specific task-dependent network. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 430–430. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00430

Disclaimer

NeoRhythm has not been evaluated by the FDA. These products do not claim to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any medical conditions. Always consult your medical doctor regarding any health concerns.