Pineal gland

Anatomy and Physiology of the Pineal Gland: – The pineal gland is a small, pine cone-shaped endocrine gland located in the brain. – It is […]

Anatomy and Physiology of the Pineal Gland:

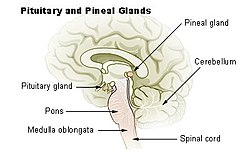

– The pineal gland is a small, pine cone-shaped endocrine gland located in the brain.

– It is situated near the center of the brain, between the two hemispheres.

– The gland secretes melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles.

– Melatonin production by the pineal gland helps regulate the circadian rhythm and influences seasonal biological rhythms.

– The pineal gland interacts with the hypothalamus to control hormone release and other bodily functions.

– The gland receives signals from the eyes regarding light and darkness to regulate melatonin production.

Clinical Aspects of the Pineal Gland:

– Calcification of the pineal gland is common in young adults and can inhibit the development of reproductive glands.

– Pineal gland calcification affects melatonin synthesis and can be detected through imaging techniques like CT scans.

– Pineal tumors are rare, with germinomas being the most common type, and can cause symptoms such as headaches, vision problems, and hormonal imbalances.

– Surgical removal of pineal tumors is challenging due to their location, and treatment may involve radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

– Regular monitoring and medical management are essential for individuals with pineal gland disorders.

Historical and Cultural Significance of the Pineal Gland:

– The pineal gland’s secretory activity has been partially understood throughout history, with early descriptions dating back to Greek physician Galen.

– René Descartes identified the pineal gland as the principal seat of the soul, attributing importance to its location in the brain.

– Melatonin was isolated and named in 1958, leading to advancements in chronobiology.

– The pineal gland has been referenced in cultural and religious contexts, with associations to concepts like the third eye and mystical properties in various works of literature and media.

– Evolutionary history explains the presence of the pineal gland in most vertebrates, with exceptions in primitive vertebrates.

Scientific Discoveries and Research on the Pineal Gland:

– Scientific discoveries include the identification of the pineal gland’s role in melatonin production and its function in regulating sleep-wake cycles.

– Ongoing research explores the impact of melatonin on mental health conditions like depression and its association with aging and age-related health consequences.

– Animal models and clinical studies provide insights into the therapeutic benefits of melatonin.

– The pineal gland function was the last of the endocrine organs to be discovered, and studies continue to investigate its physiological processes.

– Research examines the neuroendocrine effects of light, melatonin’s significance, and its chronobiotic effects on sleep and circadian rhythms.

Blood Supply, Afferents, and Other Conditions Affecting the Pineal Gland:

– The pineal gland is not isolated by the blood-brain barrier and has profuse blood flow, primarily from choroidal branches of the posterior cerebral artery.

– Afferent nerve supply involves sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways from ganglia like the superior cervical ganglion and trigeminal ganglion.

– Pineal gland morphology varies in conditions like obesity and primary insomnia, impacting gland function.

– Pathological conditions can affect gland size and shape, with ongoing research exploring the impact of these conditions on the pineal gland.

– Skull X-rays often show calcified pineal glands, with calcification rates varying widely by country.

The pineal gland (also known as the pineal body or epiphysis cerebri) is a small endocrine gland in the brain of most vertebrates. In the darkness the pineal gland produces melatonin, a serotonin-derived hormone, which modulates sleep patterns following the diurnal cycles. The shape of the gland resembles a pine cone, which gives it its name. The pineal gland is located in the epithalamus, near the center of the brain, between the two hemispheres, tucked in a groove where the two halves of the thalamus join. It is one of the neuroendocrine secretory circumventricular organs in which capillaries are mostly permeable to solutes in the blood.

| Pineal gland | |

|---|---|

Pineal gland or epiphysis (in red) | |

Diagram of pituitary and pineal glands in the human brain | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Neural ectoderm, roof of diencephalon |

| Artery | Posterior cerebral artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandula pinealis |

| MeSH | D010870 |

| NeuroNames | 297 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1184 |

| TA98 | A11.2.00.001 |

| TA2 | 3862 |

| FMA | 62033 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The pineal gland is present in almost all vertebrates, but is absent in protochordates in which there is a simple pineal homologue. The hagfish, considered as a primitive vertebrate, has a rudimentary structure regarded as the "pineal equivalent" in the dorsal diencephalon. In some species of amphibians and reptiles, the gland is linked to a light-sensing organ, variously called the parietal eye, the pineal eye or the third eye. Reconstruction of the biological evolution pattern suggests that the pineal gland was originally a kind of atrophied photoreceptor that developed into a neuroendocrine organ.

Ancient Greeks were the first to notice the pineal gland and believed it to be a valve, a guardian for the flow of pneuma. Galen in the 2nd century C.E. could not find any functional role and regarded the gland as a structural support for the brain tissue. He gave the name konario, meaning cone or pinecone, which during Renaissance was translated to Latin as pinealis. In the 17th century, René Descartes revived the mystical purpose and described the gland as the "principal seat of the soul". In the mid-20th century, the real biological role as a neuroendocrine organ was established.